Monday, April 30, 2018

Why books by Langston Hughes and Adrian Matejka appeal to high school black boys, collegiate black men

Adrian Matejka will deflect any comparison to Langston Hughes, mainly pointing out that no contemporary poet comes close to matching Hughes's body of work and his influence on American and African American literature and culture. Understood and agreed. However, in the worlds of high school black boys and black men college students where I reside, it's worth mentioning Hughes and Matejka in the same sentences.

When I organize annual book fairs for the language arts conferences I organize for high school black boys, I always include copies of books by Hughes and Matejka. The high school students have always already heard of Hughes, so they are excited to grab a free copy of one of his books. The high school students usually haven't heard of Matejka, but my college guys are there, and they always recommend The Big Smoke.

I've taught several different volumes of poetry over my years as a professor, but none has been as popular among black collegiate men as Matejka's The Big Smoke -- a volume of poetry about the first black heavyweight boxing champion Jack Johnson. The volume of poetry opens possibilities for us to have extended conversations about bad men, athletes facing racism, and various related poets and poems.

The book by Hughes give the young students a chance to acquire a full volume by a poet that they may have read only one or two poems by. The Matejka book gives them a chance to consider a volume of poetry by this talented, bodacious, and unruly historically significant black man. For some reason, that makes the book really appealing to the high school black boys and collegiate black men.

Related:

• Langston Hughes

• Adrian Matejka

Street Lit as an economic backbone of African American Lit.: A data project

By Jacinta R. Saffold

At the 2018 College Language Association (CLA) conference, I presented findings from my Essence Bestsellers digital humanities project. I generated a dataset from the fiction bestsellers list published in Essence from 1994 through 2007 as an attempt to validate the following argument: Street Lit*, despite controversy of appropriateness, was the economic backbone of African American literature at the turn of the new millennium.

My original research plan was to use book sales data collected from publishers and big box retailers to compare the economic heft and dexterity of the highest selling Street Lit novels to more academically accepted African American literature. The purpose was to put authors like Sister Souljah and her debut novel, The Coldest Winter Ever in conversation with widely lauded authors like Toni Morrison as a personal act of resistance to the boundaries that keep “canonical” African American literature separate from the inconvenient stories of urban peril and blackness in Street Lit.

However, most Street lit books were often independently produced and sold and therefore were not funneled through major clearing houses that kept meticulous sales records. Without having complete and reliable sales data, I shifted my focus to the comparative data provided within the monthly hardcover and paperback fiction ranked lists in Essence by digitizing the list using software that would allow me to disaggregate the data.

The dataset revealed interesting narratives about how Street Lit books have been packaged and sold. Sister Souljah’s The Coldest Winter Ever for example, was the longest running title on the fiction paperback chart—appearing a total of thirty-six times or the equivalent of three years and was consecutively listed for twenty-nine months. The book retailed at 35% lower than the average fiction paperback on the list in 2000 (the year of its publication). The Coldest Winter Ever demonstrated that hardcover books with sticker prices of $20 and up were extremely hard to sell to a Street Lit and Hip-Hop demographic. Portable and cheap pulp books that averaged between $5 and $12 flew off the shelves of independent bookstores alternatively.

As African American literature production progresses through the twenty-first century and we enter a new phase replete with born digital publishing, robust social media, and declining casual readers, the field is once again being called to find innovative avenues to not only to subsist in American popular culture but to also prosper. And it is our job as researchers to find the tools necessary to answer the tough questions and chart Black literature’s history in the best ways we know how.

----

Note:

* Street Lit is a contemporary popular African American literature genre that began in the early 1990s with the technological advances in home computing and personal printing as a creative response to the harsh realities of urban living in America and is a cultural cousin to Hip Hop.

Related:

• Black women scholars, digital humanities, and the College Language Association convention, 2018

• Data Mining the Norton Anthology of African American Literature - Jade Harrison

• A data project on Amiri Baraka and Sonia Sanchez - Rae'Jean Spears

The Black Anthology Project (iLASR Seed Grant)

By Kenton Rambsy

In August 2017, I was awarded a iLASR grant from the University of Texas at Arlington’s College of Liberal Arts for my project, “The Black Anthology Project.” Over the past nine months, I worked closely with two research assistants—Jade Harrison and Rebecca Newsome—to transcribe over 100 anthology tables of contents and create page level metadata to track the circulation of black texts in anthologies. Admittedly, this project was more time consuming and labor intensive than I originally assumed.

I initially thought I might use OCR software to transcribe the data, but I quickly realized that process was not a feasible option. Many tables of contents are arranged for an aesthetic appeal with different typefaces. After using OCR on a few anthologies, we had to spend a considerable amount of time editing and re-typing sections of texts in order to enter the information into the spreadsheets. After about 2 weeks, my research assistants and I found it much more efficient to transcribe the documents by hand.

From October 2017 to March 2018, we transcribed 100 tables of contents and created a dataset with the information. At the beginning of March, we started cleaning and organizing the massive amount of data in .csv files. We also started adding additional data to the information we transcribed from the tables of contents such as author birth years, author gender, original publication date of entry, and other useful descriptive metadata.

Recent coverage on Kevin Young

Back in November 2017, I wrote about the coverage of Kevin Young and his then new book. It was rare, I noted, for a poet to gain that level of attention. Well, here we are again, some months later, and Young has a new book, and there's more coverage.

A roundup:

• January 5: We have to Trust Our Punch - Ryan Krull - The Rumpus

• March 19: Brown - Publishers Weekly

• April 16: Scorching, Sophisticated Work From Two Leading Poets - Dwight Garner - New York Times

• April 16: "Nightstick [A Mural for Michael Brown]" - Kevin Young - Poets.org

• April 17: Why Kevin Young's Brown poems are not only beautiful, but essential

• April 17: Kevin Young Strolls Through Black History - Karen R. Long - Anisfield-Wolf

• April 17: Kevin Young - Poetry Daily

• April 17: "Rumble in the Jungle" - Kevin Young - Poetry Daily

• April 17: Brown - L. Ali Khan - New York Journal of Books

• April 18: Poet will give a free reading in Wichita; he's kind of a big deal - Suzanne Perez Tobias - Wichita Eagle

• April 22: Kevin Young Has Had Just About Enough of This Bullshit - Talmon Joseph Smith - Village Voice

• April 25: Kevin Young Examines All Things 'Brown' - Karen Grigsby Bates - NPR

• April 26: Poetry Collection Squints Hard at the Culture, in Pain and in Joy - Luis Alberto Urrea - New York Times

• April 26: 10 New Books We Recommend This Week - New York Times

• April 26: Filtering American History Through a 'Brown' Lens - Karen Grigsby Bates - NPR

• April 26: Brown - Melanie Dunea - NPR

Related:

• Tracy K. Smith and Kevin Young in the New York Times

• Duos of poets -- Evie Shockley & Patricia Smith, Tracy K. Smith & Kevin Young -- in the news

• Recent coverage on Kevin Young (2017)

• Poetry News Coverage in 2011

• Kevin Young

Sunday, April 29, 2018

Tracy K. Smith and Kevin Young in the New York Times

|

| Tracy K. Smith source; Kevin Young source |

African American poets don't, relatively speaking, appear that much major news outlets like The New York Times. So I've taken note of the repeated coverage of Tracy K. Smith and Kevin Young in the newspaper over the last month. Here's a quick rundown of their appearances:

• March 20: the Times ran an interview with Smith.

• April 10: Ruth Franklin published an extended profile on Smith for the Times magazine.

• April 16: Dwight Garner published a review of Smith's and Young's new volumes of poetry, Wade in the Water and Brown, respectively.

• April 19: the Times published an interview conducted by Maria Russo featuring Smith and Jacqueline Woodson.

• April 26: Charles Simic published a review of Smith's new volume of poetry.

• April 26: Luis Alberto Urrea published a review of Young's Brown.

• April 26: the Times offered "10 New Books We Recommend This Week," including Smith's and Young's books.

And that's just in the Times. Several articles have appeared on Smith and Young in various other venues over the last month as well.

Related:

• Duos of poets -- Evie Shockley & Patricia Smith, Tracy K. Smith & Kevin Young -- in the news

• Recent coverage on Kevin Young (2017)

• Poetry News Coverage in 2011

• Kevin Young

Saturday, April 28, 2018

Dynamic black women speakers vs. flat sounding poets

Given the relatively small audiences for print-based poetry, reviewers are less likely to publish negative assessments. In addition, as many poets have informed me off the record, it could jeopardize one's career as a poet to speak too truthfully in an unfavorable way about various poets. That's all quite understandable. However, the absence of public, thorough critiques makes it difficult to develop an awareness of why some college students express disdain toward the sounds of some poetry.

In the majority of cases when I hear teachers and professors talking about students disliking important poets, or finding the sound of the poetry boring, the deficiency is placed on the students. They just don't understand literature, I've been told. Or, they are too influenced by popular culture. Maybe so. However, findings from a recent research project suggest other possibilities as well.

In their article "Beyond Poet Voice," researchers Marit J. MacArthur, Georgia Zellou, and Lee M. Miller sampled 100 poets -- 50 men and 50 women -- reading one of their poems. The researchers noted commonalities and differences among the poets. They also noted relationships of the poets in relation to samples of conversational speech.

The researchers found that, on average, the poets were less expressive in their readings than the sample of people in conversational speech. They also discovered that for the most part, women poets are more expressive than men poets during readings. At the same time though, women poets differed more from women in conversational speech than men poets differed from men in conversational speech.

Those findings are really worth considering if you work with large numbers of black college students.

For more than a decade now, I have taught a series of classes comprised of all black men and classes comprised of all black women. The variety of speaking styles, dynamism, volumes, paces, and other measures of expressiveness have been far more pronounced in the classes of first-year black women students. By their own descriptions, some of them talk "white," "proper," "hood," "ghetto," "real black," and "black but not too black."

As a group, my first-year black women laugh out loud much more than any other grouping of my other students. Individuals among the group will demonstrate the way other kinds of black women talk, and speakers among this group are more likely to playfully mock the ways that "white girls" and "black dudes" talk. In short, my first-year black women are more infinitely more interesting speakers than any of my other students, including my junior and senior black women students.

Could the complex and vibrant conversational speaking styles of my first-year black women students explain why they typically find formal poetry readings by prominent black women poets so unappealing? I think so. Accordingly, could the lack of major differences between men poetry readers and men in conversational speech explain why my black men students are less vocal in their displeasure with black men poets than my black women students? Perhaps.

Not surprisingly, my black women students express more fondness for spoken word artists, who tend to be younger, than for formal poets. The spoken word artists are typically more expressive than the formal poets. In some cases, spoken word artists are known to adopt conversational performance approaches, and their dramatic reading styles are ultimately more dramatic than the style often associated with academic-style "poet voice," which often characterized as sounding flat.

For the most part, the professors who are most likely to publish scholarly articles about poetry tend to work with relatively few black women students. On the other hand, the professors who work with large numbers of black women students encounter more barriers to scholarly publishing (i.e. heavy teaching loads and few resources). As a result, there's a gap in our collective knowledge on poetry.

However, if we are to fully appreciate how and why black women students respond to poetry the ways that they do, then we could do more to take into account their conversational speech patterns.

Related:

• Why some black poetry sounds boring to black students (abstract)

• A Notebook on Readers

Friday, April 27, 2018

The Sound Studies conference at University of Wisconsin-Madison -- brief summary, reflections

I often judge the value of a conference based on how intellectually stimulated I am and prompted to try new things and move in new useful directions with my work -- in the scholarship and classroom. By that measure, the recent Great Lakes Association for Sound Studies (GLASS) conference that took place at the University of Wisconsin-Madison on April 20 and 21, was of immense importance. I'm still excited about all I learned.

The conference, hosted by Jeremy Morris, Jeff Smith, and Neil Verma included presentations on podcasting, software for analyzing the pitch, pace, and dynamism of poetry, the multi-modal practices of blind readers, ASMR YouTube videos, how sound designers translate animated films from one country to another, a recently digitized trove of dictabelts from the Rod Sterling collection, instruction on pronunciation of r's in stage and screen productions, and more.

The information on podcasts were especially plentiful. There were four different presentations about podcasts, as well as a live performance of the podcast Field Notes produced by Craig Eley. He presented an upcoming episode "Reading by Ear" of his podcast, drawing on research by Mara Mills that focused on how blind readers utilized "pre-computer technologies that translated ink print into synthesized tones," making use of "tonal alphabets."

The keynote was by Mara Mills, who discussed impairment, "a central term in Anglophone disability studies," in relation to a number of findings she has made researching connections between "AT&T (American Telephone & Telegraph) and the public health field."

In the abstract for his opening presentation on podcasting, Morris offered a perspective that could have been a kind of guiding idea for the conference. He urged researchers "to consider sound as scholarship and what might be possible" when sonic items and artifacts are "analyzable."

Given all the work I do with audio recordings, it's odd and unfortunate that I have not been part of more gatherings like these where there was so much discussion of sound and audio recordings. I presented on the topic of "why some black poetry sounds boring to black students." My future writings and presentations on the topic will be better as a result of attending this GLASS conference.

For one, the participants were encouraging me to think well beyond exposing my students to recordings of poetry in my classes. Why not also present, for instance, excerpts from podcasts, audio of actual conversations, and the strange and interesting world of ASMR YouTube videos? In addition, the conversations about the challenges and opportunities for preserving podcasts inspired me to think more about archiving and organizing the various recordings I've collected over the years.

The setup of the conference also worked well. Over the course of two days, there were 7 sessions with approximately 17 presenters, consisting of professors, graduate students, an independent computer scientist, and an audio producer and administrator. There was plenty of time for discussion after each of the presentations. There were perhaps 35 to 45 people in attendance.

Related:

• A notebook on conferences

Why some black poetry sounds boring to black students (abstract)

I recently gave a presentation, "Why some black poetry sounds boring to black students" at the Great Lakes Association for Sound Studies conference, which took place at the University of Wisconsin-Madison on April 20 and 21.

Here's my abstract:

This presentation increases our knowledge of sound studies by taking into account the agency of African American student listeners. The scholarly discourses on American and African American literature devote relatively little attention to the perspectives of black students. Nonetheless, the disparagement of poet voice or what was more commonly referred to as “boring” sounding poetry among the large number of black students I worked with over the years motivated me to expand the range of recordings I obtained and presented. My presentation explains my efforts over the last several years utilizing audio recordings of African American poets while working with black students at the collegiate and high school levels. A consideration of student responses to poetry that they find uninteresting on the one hand and poetry they find captivating on the other might assist us in developing curriculums and sound archives that are ultimately more diverse and inclusive.---------------

I've been thinking and blogging about the topic for a while based on my experiences covering audio recordings of African American poetry with my students over the last decade.

Related:

• Understanding the favorite poets of black women students

• Why some collegiate black women might find contemporary black poetry boring

A notebook on conferences

A roundup of write-ups I did on conferences I attended.

2018

• The Sound Studies conference at the University of Wisconsin-Madison -- brief summary, reflections

• Black women scholars, digital humanities, and the College Language Association convention, 2018

2017

• Dispatches from Cultural Analytics symposium

• Black women scholar-organizers and literary gatherings

2016

• A few lessons from the Toni Morrison Society Conference

2015

• A Notebook on Black Poetry After the Black Arts Movement

2013

• Digital Humanities at CLA 2013

• The value of a small scholarly gathering

• Representing Race: Silence in the Digital Humanities

• Conference Notes: U.S. and Afro-Caribbean Poetry at Penn State

2012

• Black Thought 2.0

2010

• HBCUs and MLA

• Black men and MLA

• The Division on Black American Lit. & Culture

• Black Studies and Digital Humanities

• Film Studies, Black Studies, & Digital Humanities

2009

• Digital Humanities as "the Next Big Thing"?

Related:

• Assorted Notebooks

2018

• The Sound Studies conference at the University of Wisconsin-Madison -- brief summary, reflections

• Black women scholars, digital humanities, and the College Language Association convention, 2018

2017

• Dispatches from Cultural Analytics symposium

• Black women scholar-organizers and literary gatherings

2016

• A few lessons from the Toni Morrison Society Conference

2015

• A Notebook on Black Poetry After the Black Arts Movement

2013

• Digital Humanities at CLA 2013

• The value of a small scholarly gathering

• Representing Race: Silence in the Digital Humanities

• Conference Notes: U.S. and Afro-Caribbean Poetry at Penn State

2012

• Black Thought 2.0

2010

• HBCUs and MLA

• Black men and MLA

• The Division on Black American Lit. & Culture

• Black Studies and Digital Humanities

• Film Studies, Black Studies, & Digital Humanities

2009

• Digital Humanities as "the Next Big Thing"?

Related:

• Assorted Notebooks

Digital Humanities Club: Week 13

|

| Altered Henry Box Brown image from our Great Escape Project |

On April 25, we spent the last week of our Digital Humanities Club meeting discussing what we had accomplished over the course of the semester and taking suggestions about what we want to do moving forward.

I'm still processing the feedback, but I sensed that the high school students enjoyed the experience of spending time for the program on a college campus. Early on, transportation from East St. Louis to SIUE posed a challenge. However, we eventually resolved that issue.

The use of the Eugene B. Redmond Learning Center in the library was really important for us this semester. In the future, though, we'll utilize more of the campus. In retrospect, I think we may have gotten stuck behind the computers a little too much, which isn't so strange for a DH club I suppose. Next year, I want to make sure we're walking around a little more.

We'll also continue working on our Great Escape Project. Having a set project, as opposed to only freestyling, gave us a necessary focus and a sense of purpose. We'll build on that.

Related:

• The East St. Louis Digital Humanities Club Spring 2018

Thursday, April 26, 2018

Understanding the favorite poets of black women students

The literary scholar Jerry W. Ward, Jr. was recently raising a question, prompting me to think about general audiences: "What do we find proof of in print and online sources that are not in 'prominent scholarly journals?'" His question responded to something I had previously noted about the topics academics covered in scholarly contexts. But what about, Ward was asking, audiences, especially black general audiences, beyond the scholars? (It's worth noting that Ward has been actively formulating questions and making observations about those black audiences for over 35 years now, like his inquiry, "why do Black readers read what they read when they read?"

One body of evidence on responses to black poetry might be in the realm of what is broadly referred to as spoken word. It's likely, by the way, that the term "spoken word" inadequately captures the shifts in that discourse over the last two decades. To respond to Ward's initial question though, we find proof of audiences in those spoken word areas who find value in vocally complex or dynamic performances on subjects that are biting, serious, and comedic.

With few exceptions, award-winning black women poets in spoken word environments are largely separate from award-winning black women poets who are praised often praised based on their volumes of poetry and close proximity to powerful institutions, like universities and fellowship and prize-granting organizations. Those spoken word poets remain invisible to many scholars who use books as their main sources for studying and teaching poetry.

I was aware of spoken word artists many years ago while in undergrad, but I have remained mindful of the emergence of new artists based on my communications with mostly my black women students. When and if I present my classes with works by canonical poets like Gwendolyn Brooks and Sonia Sanchez, or contemporary writers like Evie Shockley and Elizabeth Alexander, my students listen and take notes. However, whenever I present work by spoken word artists, individual black women students will approach me after class, suggest additional spoken word artists to consider, and later email me a YouTube link or two of the poet they have in mind. (As a contrast, my black men students tend to email me YouTube links of underground rappers that they think I should consider).

Over the last few years, black women students sent me dozens of YouTube links of their favorite poets. Relatively few of their favorite poets were over the age of 30, and none of those poets are among the canonical poets discussed in the scholarly discourse, nor are any of those poets the dozens of award-winning black women poets I've charted in past entries.

The very act of students emailing their professor YouTube links of black women poets "you should hear" provides proof of a distinct technological mode of sharing poems. The links they provide me show black women poets reading at slam competitions or at local venues for poetry. The readings themselves are often interrupted by shouts, vocal affirmations, and laughter when the poets make powerful or biting statements, providing evidence that readings in these environments are interactive and sometimes rowdy. The readings, in other words, are a contrast from the quiet, staid poetry readings that occur in academic contexts.

It's not just the performance styles though. Those favorite poets that students pass along tend to address the dramas of being black women in contemporary environments in ways that leading poets in academic contexts don't, at least not as much. For instance, in one of her poems, Jae Nichelle catalogs the cruel insults expressed by black and white people about her lips. Emi Mahmoud opens her poem "Mama" by recalling the ways that a man on the streets tried to disrespectfully flirt with her.

Listen to enough of poets in these realms, and you get a sense that expressiveness, righteous rage, humor, and contemporary interactions between black men and women are central aesthetics and themes. The emphatic and diverse delivery styles also suggest why many of my black women students find the poetry boring that they are exposed to by high school teachers and college professors. While I respect the work that we -- teachers and professors -- are doing, I admit that so much of it is relatively flat in comparison to the kinds of poetry that the students value.

Related:

• A Notebook on Readers

Friday, April 20, 2018

Public Thinking Event (managing conflict)

For our Public Thinking Event on April 18, we coordinated the initial phase of a project related to managing conflict. We introduced students to a series of different kinds of ways that people respond to conflicts. We then asked them to identify the kinds of conflict management styles that they were drawn to. We also prompted them to imagine different approaches. In sessions next year, we plan to follow up on the results.

Related:

• Spring 2018 Programming

Thursday, April 19, 2018

Notes on "Beyond Poet Voice"

Last year, I heard a fascinating presentation by scholar Marit J. MacArthur, where she discussed some ongoing work that she's doing utilizing digital tools to analyze sounds and speech patterns of American poets. I wrote about some of her research and findings, and how that connects with my own work. MacArthur and her colleagues Georgia Zellou and Lee M. Miller just recently published an article, "Beyond Poet Voice: Sampling the (Non-) Performance Styles of 100 American Poets" for the Journal of Cultural Analytics. I am particularly intrigued with their treatment of black women poets.

Overall, the article explains how MacArthur, Zellou, and Miller took an empirical look at the performance or reading styles of poets. They base their research on a sample of recorded poems by 100 poets. They examine differences between groups of poets, and they seek to quantify what is known as Poet Voice through the use of digital tools. For someone like me, who's been spending way too much time thinking about the implications of how poets sound and present their work, the work that these scholars are doing is really important.

And not just the examination of sounds with poetry. I also appreciate that they use a relatively large sample-size (in the realm of poetry studies at least) to address their concerns. At one point, they note that humanities scholars "are adept at generating broadly persuasive insights from a few choice examples." Literary scholars have done less, though, to look at datasets of 50 and 100 writers at a time to produce various insights.

Alright, but where I was really drawn in and excited about this project concerned the specific analyses of women and African American poets, and especially black women poets. MacArthur, Zellou, and Miller found that the 50 women poets in their sample exhibit "a wider pitch range, faster pitch speed, slightly faster pitch acceleration, and greater dynamism overall." Furthermore among the women, they discovered useful findings concerning black women poets.

For one, they note that "seven of the ten female poets with the highest values for dynamism are African-American poets born before 1960, some associated with the Black Arts movement." Those black women are Wanda Coleman, Sonia Sanchez, Harryette Mullen, June Jordan, Lucille Clifton, Jayne Cortez, and Rita Dove. Excluding Dove, six of those black women poets have the "fastest pitch speed," and five of them "are also among the ten female poets with the fastest pitch acceleration." And, three of those black women poets -- June Jordan, Sonia Sanchez, and Jayne Cortez -- "are also among the fastest in terms of speaking rate."

So, black women poets are on one far side of dynamism, pitch speed, pitch acceleration, and speaking rate. Fascinatingly, black women are on the other end as well. The scholars observe that "five of the ten sampled recordings of female poets with the lowest values for dynamism are also African-American ... They are: Tracy K. Smith, Natasha Trethewey, Audre Lorde, Toi Derricotte, Claudia Rankine, and Elizabeth Alexander." What does it mean that black women poets comprise the highest and lowest levels of dynamism in a sample of 50 American women poets and 100 American poets?

It's worth noting that Smith, Trethewey, and Alexander are among our most decorated African American poets. Rankine's book Citizen is perhaps the best selling poetry book over the last several decades. All of that is to say that certain kinds of literary prominence do no correlate to reading performance dynamism. Or, perhaps -- and the work by MacArthur, Zellou, and Miller leads me to this idea -- low expressiveness in poetry readings is one of the requirements of being a major award-winning black woman poet?

For about a decade now, I've taught a class that enrolls first-year black women students. The empirical findings in "Beyond Poet Voice" correspond with the general and intuitive observations of my students in those classes. In short, some of the students express a lack of interest in poets that they feel lack dynamism. This article by MacArthur, Zellou, and Miller signals some possibilities for quantifying what black women students are hearing.

-----------

I'll provide more on this article in future entries.

Notes on "Beyond Poet Voice"

Last year, I heard a fascinating presentation by scholar Marit J. MacArthur, where she discussed some ongoing work that she's doing utilizing digital tools to analyze sounds and speech patterns of American poets. I wrote about some of her research and findings, and how that connects with my own work. MacArthur and her colleagues Georgia Zellou and Lee M. Miller just recently published an article, "Beyond Poet Voice: Sampling the (Non-) Performance Styles of 100 American Poets" for the Journal of Cultural Analytics. I am particularly intrigued with their treatment of black women poets.

Overall, the article explains how MacArthur, Zellou, and Miller took an empirical look at the performance or reading styles of poets. They base their research on a sample of recorded poems by 100 poets. They examine differences between groups of poets, and they seek to quantify what is known as Poet Voice through the use of digital tools. For someone like me, who's been spending way too much time thinking about the implications of how poets sound and present their work, the work that these scholars are doing is really important.

And not just the examination of sounds with poetry. I also appreciate that they use a relatively large sample-size (in the realm of poetry studies at least) to address their concerns. At one point, they note that humanities scholars "are adept at generating broadly persuasive insights from a few choice examples." Literary scholars have done less, though, to look at datasets of 50 and 100 writers at a time to produce various insights.

Digital Humanities Club: Week 12

On April 18, we experimented with audio recordings, and we continued working on graphic design imaging for what will be our "great escape" project visuals. Having a clear project in mind has been helpful. It also helps that we've tried to think about distinct audiences a little more.

The students worked with images of Harriet Tubman, and we talked about ways that we might incorporate her image and ideas about her leading so many people to freedom into our project. How do you update or alter images of Tubman in ways that suggest something about her powers in sci-fi ways? We're still working through answers.

Related:

• The East St. Louis Digital Humanities Club Spring 2018

Wednesday, April 18, 2018

Haley Reading Groups: reflections

[The Best American Science and Nature Writing (2016)]

Over the last few months, we read and commented on:

• January 24 Amanda Gefter's "The man who tried to redeem the world with logic”

• January 31 Apoorva Mandavilli’s “The Lost Girls”

• February 14 Charles C. Mann’s “Solar, Eclipsed”

• February 28 Rinku Patel’s “Bugged”

• March 21 Gaurav Raj Telhan's “Begin Cutting"

• April 4 Katie Worth’s “Telescope Wars”

What article most challenged your thinking? That is, which article, among those we read, prompted you to most re-think preconceived ideas or stretch your mind in new ways? How so?

Haley Reading Group: reflections

[The Best American Science and Nature Writing (2015)]

Over the last few months, we read and commented on:

• Sheri Fink’s “Life, death, and grim routine fill the day at a Liberian Ebola ClinicWhat article most challenged your thinking? That is, which article, among those we read, prompted you to most re-think preconceived ideas or stretch your mind in new ways? How so?

• Eli Kintisch's “Into the Maelstrom”

• Sam Kean’s “Phineas Gage, Neuroscience’s Most Famous Patient”

• Jourdan Imani Keith’s “At Risk" & “Desegregating Wilderness”

• Dennis Overbye’s “A Pioneer as Elusive as His Particle”

• Michael Specter’s “Partial Recall”

Monday, April 16, 2018

Duos of poets -- Evie Shockley & Patricia Smith, Tracy K. Smith & Kevin Young -- in the news

This morning, Times ran a dual review of new volumes of poetry by Tracy K. Smith and Kevin Young. It's not everyday that the Times runs reviews of work by African American poets, so I was especially intrigued that here was a review featuring, not one but two.

Ok, next up, the Pulitzer Prize winners were announced today. Patricia Smith's Incendiary Art and Evie Shockley's semiautomatic were finalists in the poetry category. What a moment! Two black women as finalists for a Pulitzer Prize in poetry. I don't think there have ever been two black finalists in the poetry category before, and here we have two black women. Big congratulations to them both.

Related:

• Tyehimba Jess wins Pulitzer Prize for Poetry

• Margaret Walker almost won the Pulitzer in 1943

• Does the Pulitzer award for poetry favor "younger" black poets?

• The Coverage of Tracy K. Smith's Pulitzer-Prize Win

A data project on Amiri Baraka and Sonia Sanchez

By Rae'Jean Spears

In my presentation at the College Language Association (CLA) conference, I interrogated the idea of the "widely anthologized poet." The presentation was based on a dataset on two poets, Amiri Baraka and Sonia Sanchez, that I have been working on with Professor Howard Rambsy. The presentation contends that literary scholars can illuminate studies of major writers like Baraka and Sanchez by utilizing data management software to track a wide array of publishing information – beyond conventional bibliographies.

By using quantitative data in this capacity, I offer that literary scholars are able to further conversations on how writers are published differently across the overall American literary canon. To support my position, I drew from our dataset of approximately 60 anthologies published between 1960 and 2016.

Those anthologies collectively printed Baraka’s poems 252 times. More than 50 of his poems, however, appear only once. Three of Baraka’s poems “Preface to a Twenty Volume Suicide Note,” “A Poem for Black Hearts,” and “Black Art” appeared in more than 10 anthologies. In these same 60 anthologies, Sanchez only appears in 35. Sanchez’s poems appear 108 times, less than half of 252 times that Baraka's poems appeared. Sanchez’s poem “poem at thirty” was her most frequently reprinted.

Including quantitative data, rather than solely qualitative observations, challenges scholars to expand our thinking of our respective research projects. Doing a dataset of both Sanchez and Baraka provided me with a more holistic view of how their contributions to the canon have been received. In doing this project, I often wondered, are Baraka and Sanchez major figures in poetry outside of African American literary spaces?

My analyses leads to the conclusion that scholars can advance the study of Baraka, Sanchez, and black writers in general by incorporating approaches that seek to account for how little of a writer’s overall work is published, the trends surrounding what is published, and how editors play a significant role in the literary portrayal of black writers.

Data Mining the Norton Anthology of African American Literature

By Jade Harrison

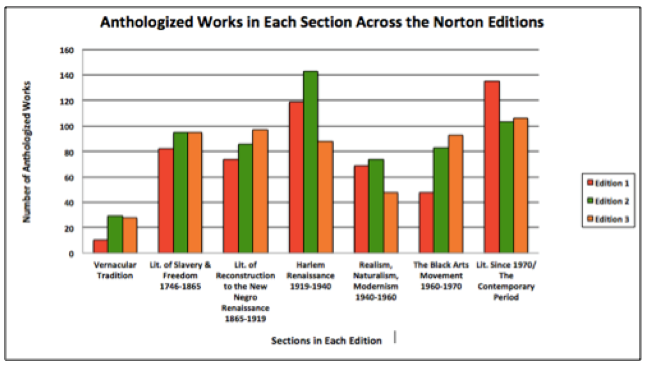

On Friday, April 6, 2018, at the College Language Association (CLA) conference, I presented my paper “The Black Anthology Project” on a digital humanities panel. In September 2017, I started working on the Black Anthology Project directed by Professor Kenton Rambsy. The goal of the project is to create a digital record concerning the contents of 100 anthologies, published over several decades.

In my presentation, I provided a handout to audience members where I charted some of my findings from my analyses of the three editions of the Norton Anthology of African American Literature (1997, 2003, 2014). These preliminary findings compared the appearances of men and women authors in the editions.

In figure 1.2, I’ve noted that “The Harlem Renaissance” and “The Black Arts Movement” contain relatively fewer literary works written by women authors than men. Works such as “Lady, Lady” by Anne Spencer, “My Little Dreams “ by Georgia Douglass Johnson, and 4 four chapters of Nella Larson’s Quicksand are removed after the first edition.

Similarly, in the Black Arts Movement section (Figure 1.3), the number of entries by men writers rises consistently across the three editions from 37 entries to 56 entries. The number of anthologized works by women authors rises from 11 entries in the first edition to 38 entries in the second to fall again to 37 entries in the third edition. Works such as “Railroad Bill, A Conjure Man,” and “Chattanooga” by Ishmael Reed are added after the first edition.

While the “Harlem Renaissance” and “Black Arts Movement” sections saw a disproportional representation of entries by men to women writers, the contemporary period saw a disproportional representation of women to men. The “Contemporary Period,” is the largest section of anthologized literary works across the three editions.

According to Figure 1.4, in each edition, anthologized works by women authors significantly outnumber the works included by men authors. Between 1997 and 2014, the number of works anthologized by women writers remains significantly higher than works anthologized by men. Entries by men writers decrease in “Contemporary Period” from 52 entries in the first edition, to 31 entries in the second edition, to 29 entries in the latest edition.

What does this analysis suggest? A larger number of black women writers have received widespread critical attention over the last four decades than in previous eras. Toni Morrison and Alice Walker won Pulitzer Prizes for fiction. Rita Dove, Natasha Trethewey, and Tracy K. Smith won prizes for poetry. Morrison won the Nobel. Octavia Butler gained considerable attention for science fiction.

The gender argument, alone, doesn't explain why these women got in and other women did not. My findings indicate the need for more research regarding the types of texts by black women writers that editors include.

On Friday, April 6, 2018, at the College Language Association (CLA) conference, I presented my paper “The Black Anthology Project” on a digital humanities panel. In September 2017, I started working on the Black Anthology Project directed by Professor Kenton Rambsy. The goal of the project is to create a digital record concerning the contents of 100 anthologies, published over several decades.

In my presentation, I provided a handout to audience members where I charted some of my findings from my analyses of the three editions of the Norton Anthology of African American Literature (1997, 2003, 2014). These preliminary findings compared the appearances of men and women authors in the editions.

In figure 1.2, I’ve noted that “The Harlem Renaissance” and “The Black Arts Movement” contain relatively fewer literary works written by women authors than men. Works such as “Lady, Lady” by Anne Spencer, “My Little Dreams “ by Georgia Douglass Johnson, and 4 four chapters of Nella Larson’s Quicksand are removed after the first edition.

Similarly, in the Black Arts Movement section (Figure 1.3), the number of entries by men writers rises consistently across the three editions from 37 entries to 56 entries. The number of anthologized works by women authors rises from 11 entries in the first edition to 38 entries in the second to fall again to 37 entries in the third edition. Works such as “Railroad Bill, A Conjure Man,” and “Chattanooga” by Ishmael Reed are added after the first edition.

While the “Harlem Renaissance” and “Black Arts Movement” sections saw a disproportional representation of entries by men to women writers, the contemporary period saw a disproportional representation of women to men. The “Contemporary Period,” is the largest section of anthologized literary works across the three editions.

According to Figure 1.4, in each edition, anthologized works by women authors significantly outnumber the works included by men authors. Between 1997 and 2014, the number of works anthologized by women writers remains significantly higher than works anthologized by men. Entries by men writers decrease in “Contemporary Period” from 52 entries in the first edition, to 31 entries in the second edition, to 29 entries in the latest edition.

What does this analysis suggest? A larger number of black women writers have received widespread critical attention over the last four decades than in previous eras. Toni Morrison and Alice Walker won Pulitzer Prizes for fiction. Rita Dove, Natasha Trethewey, and Tracy K. Smith won prizes for poetry. Morrison won the Nobel. Octavia Butler gained considerable attention for science fiction.

The gender argument, alone, doesn't explain why these women got in and other women did not. My findings indicate the need for more research regarding the types of texts by black women writers that editors include.

Sunday, April 15, 2018

A notebook of entries by Rae'Jean Spears

Rae'Jean Spears is a graduate student in the department of English at Southern Illinois University Edwardsville. She pursued her undergraduate studies at Tougaloo College.

2018

• April 16: A data project on Amiri Baraka and Sonia Sanchez

• April 11: Haley Reading Group: Michael Specter’s “Partial Recall”

• March 28: Haley Reading Group: Dennis Overbye’s “A Pioneer as Elusive as His Particle”

• March 21: Haley Reading Group: Gaurav Raj Telhan's “Begin Cutting"

• February 28: Haley Reading Group: Rinku Patel's "Bugged"

• February 21: Haley Reading Group: "Phineas Gage, Neuroscience’s Most Famous Patient"

• February 7: Haley Reading Group: :Into the Maelstrom

• January 31: East St. Louis DH Club Week #3 Reflection

• January 24: East St. Louis DH Club Week #2 Reflection

January 24: Haley Reading Group: "Life, Death, and Grim Routine Fill the Day at a Liberian Ebola Clinic"

January 24: Haley Reading Group: "The Man Who Tried to Redeem the World with Logic"

• January 17: East St. Louis DH Club Week #1 Reflection

2017

• December 6: East St. Louis DH Club Week #12 reflection

• November 29: East St. Louis DH Club Week #11 reflection

• November 15: East St. Louis DH Club Week #10 reflection

• November 4: East St. Louis DH Club Midterm reflection

• October 25: East St. Louis DH Club Week #7 reflection

• October 18: East St. Louis DH Club Week #6 reflection

• October 11: East St. Louis DH Club Week #5 reflection

• October 4: East St. Louis DH Club Week #4 reflection

• September 27: East St. Louis DH Club Week #3 reflection

• Setpebmer 20: East St. Louis DH Club Week #2 reflection

• September 11: East St. Louis DH Club Week #1 reflection

Related:

• Black women scholars, digital humanities, and the College Language Association convention, 2018

• Rae’Jean Spears: Notes on the first semester

• Rae'Jean Spears: the critical facilitator and conversationalist

• Black women, self-portraits, and selfies

------

• An Extended Notebook on the works of writers & artists

2018

• April 16: A data project on Amiri Baraka and Sonia Sanchez

• April 11: Haley Reading Group: Michael Specter’s “Partial Recall”

• March 28: Haley Reading Group: Dennis Overbye’s “A Pioneer as Elusive as His Particle”

• March 21: Haley Reading Group: Gaurav Raj Telhan's “Begin Cutting"

• February 28: Haley Reading Group: Rinku Patel's "Bugged"

• February 21: Haley Reading Group: "Phineas Gage, Neuroscience’s Most Famous Patient"

• February 7: Haley Reading Group: :Into the Maelstrom

• January 31: East St. Louis DH Club Week #3 Reflection

• January 24: East St. Louis DH Club Week #2 Reflection

January 24: Haley Reading Group: "Life, Death, and Grim Routine Fill the Day at a Liberian Ebola Clinic"

January 24: Haley Reading Group: "The Man Who Tried to Redeem the World with Logic"

• January 17: East St. Louis DH Club Week #1 Reflection

2017

• December 6: East St. Louis DH Club Week #12 reflection

• November 29: East St. Louis DH Club Week #11 reflection

• November 15: East St. Louis DH Club Week #10 reflection

• November 4: East St. Louis DH Club Midterm reflection

• October 25: East St. Louis DH Club Week #7 reflection

• October 18: East St. Louis DH Club Week #6 reflection

• October 11: East St. Louis DH Club Week #5 reflection

• October 4: East St. Louis DH Club Week #4 reflection

• September 27: East St. Louis DH Club Week #3 reflection

• Setpebmer 20: East St. Louis DH Club Week #2 reflection

• September 11: East St. Louis DH Club Week #1 reflection

Related:

• Black women scholars, digital humanities, and the College Language Association convention, 2018

• Rae’Jean Spears: Notes on the first semester

• Rae'Jean Spears: the critical facilitator and conversationalist

• Black women, self-portraits, and selfies

------

• An Extended Notebook on the works of writers & artists

Friday, April 13, 2018

Lost Southern Voices: Mapping Edward P. Jones’s D.C.

By Kenton Rambsy

On March 23 and 24, I participated in the Lost Southern Voices Festival hosted by Georgia State Perimeter College in Atlanta, Georgia. The event was organized by my graduate school cohort member and friend, Jennifer Colatosti along with her colleagues Pearl McHaney and Andy Rogers.

The Atlanta Journal Constitution described the literary festival as “a two-day celebration of lost and under-appreciated Southern writers” where “invited writers and scholars discuss favorite authors whose works no longer receive the attention and reading they deserve.”

In my presentation, I chose to highlight an overlooked geographic location rather than a forgotten or “lost” writer. I focused on Edward Jones’s representations of African Americans “up south” in the nation’s capital—Washington, D.C.

Despite the long history and dense population of African Americans living in or near the nation’s capital, the predominately black quadrants of Washington D.C., have a relatively small presence in the scholarship on African American literature. Jones, however, utilizes these locations and populates them with African American characters not by happenstance. Instead, he embeds his story with subtle societal traits to make the correlation between race and location more apparent.

In my presentation, I previewed a heat map from an upcoming digital publication. In 2017, I taught a graduate course, “Lost in the City,” that covered Jones’s two collections of short fiction. In the class, my students and I collaborated on a dataset that tracked all of the locations and streets mentioned in Jones’s work. One of the students in the course, Ahmed Foggie, used ArcGIS to transform our data into an interactive map.

The heat map below highlights the areas in D.C. that Jones refers to most often in his short stories. By clicking on an individual story to the left, you are able to see all of the locations mentioned in that story. The brighter the color indicates that more action took place in that particular location(s).

Jones’s constant references to street names, cultural figures, and landmarks draws on historical and social memories of D.C. for each character. These memories reveal how a select geographic location has the ability to conjure a range of emotions and thus become significant to the overall plot of each story. A map like this is particularly useful given the changing landscape of D.C. over the past two decades.

From the University of Kansas to Atlanta: Grad School Cohort Members Reunite

By Kenton Rambsy

A couple of weeks ago, I got to spend some time in my old stomping ground of Atlanta, Georgia, when one of my best friends from graduate school, Jennifer Colatosti, invited me to speak at Georgia State Perimeter University. Jennifer, an Assistant Professor of English and assistant chair of the English department at the Decatur campus, organized two events that occurred between March 22 and March 24.

On Marc 22, Jennifer organized the LIT lecture series sponsored by State Farm. In my talk, I shared interactive visualizations from my recent online book, #TheJayZMixtape to explain the overlaps between rap and traditional literature. The next two days, March 23 and 24, Jennifer was a co-organizer for the Lost Southern Literary Voices Festival. At this event of more than 30 accomplished literary scholars, I had the privilege to talk about southern literature alongside very accomplished scholars such as Professors Trudier Harris and Tony Grooms.

A photo-review of the Language Arts Conference

On April 11, we hosted our annual Language Arts conference for high school African American boys.

|

| Digital Humanities at the Language Arts Conference |

|

| Book fair, featuring illustrated works |

|

| College students take the lead at Language Arts conference |

Curating a Malcolm X digital collection

This year at our Language Arts conference, we used our tablets to look at a large selection of images of Malcolm X. The task was for participants to narrow down the selections, as if preparing a curated show of the photographs.

Malcolm X was one of our most photogenic cultural figures. He also remains popular among large numbers of black boys and young black men. So the guys really enjoyed the activity.

For me, the session was also a chance to give the students opportunities to think about themselves as curators. I've been reading about how black people are often outside the loop in museums and curated shows. What if we got them thinking about the processes of working in museums, galleries, or libraries much earlier though?

The activity also gave the students a chance to engage a digital collection of Malcolm X images. I'm not sure what kinds of activities they participate in during their regular day with tablets, but here was an opportunity to utilize the technology to consider a large number of items related to an admired black historical and cultural figure.

Related:

• Language Arts Conference, Spring 2018

College students take the lead at Language Arts conference

|

| Naseem Dove leads discussion of Black Panther covers at Language Arts Conference |

Naseem Dove is one of my more soft-spoken students. However, he was one of the leading facilitators during the conference. He led discussions, and he offered invaluable contributions during the audio composition session, as he had produced one of the more popular tracks.

|

| Jeshua, at left, leads discussion on images of Malcolm X |

Steven Gay, Jeshua Pearson, VJ Smith, Christopher Malone, Donovan Washington, Gaige Crowell, and Naseem Dove gave their time and energy in a variety of ways. They took the lead on all the sessions, and just as important engaged the high school students in conversations throughout the day.

Related:

• Language Arts Conference, Spring 2018

Book Fair, featuring illustrated works

One of my signature events for the Language Arts conference are free book fairs. Presenting students with opportunities to select books and explain some of the reasons for their selection is always a highlight.

This year, I concentrated primarily on books with visual art. Given some of the books guys chose and talked about in the past, I wanted to highlight works with images.

I acquired a few different comic books, including Noble, Accell, Destroyer, and Black Panther. Not surprising given the release of the recent film, Black Panther was a big hit for the guys. However, I noticed they were intrigued with several of the books.

|

| Student reading Accell at the book fair |

I also included The Rap Year Book and Basketball (and Other Things) written by Shea Serrano and illustrated by Arturo Torres. Their work has caught the interests of students in the past, so I was sure to include copies of their books for this fair.

Beyond those books with artwork, the guys always gravitate toward The Autobiography of Malcolm X. It's been fascinating to me that year after year that book always piques the interests of high school black boys. I'm always inclined to purchase more copies for the free fair, as I know guys will pick it up and ask questions about the book.

Related:

• Language Arts Conference, Spring 2018

Digital Humanities at the Language Arts Conference

I've coordinated Language Arts conference over the last few years, but this was the first time that I used student-created compositions for the sessions. For two different activities, I utilized works produced by participants in the East St. Louis Digital Humanities Club -- an after-school program that involves high school and college students in products related to technology.

One of our sessions gave conference attendees the opportunity to listen to a selection of audio productions, which blended instrumentals with excerpts from poetry and statements from Malcolm X. All of the productions were produced by the DH club participants as well as one of my undergraduate students, Naseem Dove.

For another session, attendees took a look at "escape ads" -- creative blends of short narratives and images focused on tales of runaways fleeing enslavement through the use of special powers. The narratives for the project were composed by creative writer and professor Geoff Schmidt, and the visuals were produced by members of our DH club.

The high school attendees at the conference were intrigued to learn that students just like them had produced the audio and visual compositions for the sessions.

Related:

• Language Arts Conference, Spring 2018

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)