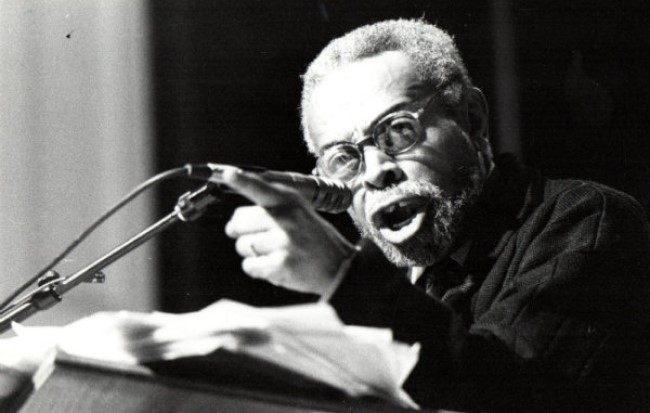

The poem and perhaps more specifically Baraka's performance of the poem really move students. The content has not changed over the years, but students have. They arrive to the poem with less knowledge about the references he makes to various people and things.

For instance, when I covered the poem in the early 2000s, more of the students were aware of Roots and The Jefferson's, which Baraka mentions. My students in class today were born in 2004, so they needed me to tell them about more references than my students 10 and 18 years ago.

Still, across the years, the many students who are mesmerized by Baraka's reading have remained constant. Some laugh when Baraka goes "uuuuuu," at the beginning. Others are amused by the "owow."

Students are shocked and intrigued by Baraka mocking a preacher, especially with his repeated use of the line "put your money in the plate." Th guys say they've never come across a poem in a classroom setting where the poet is so overtly and comically critical of black Christianity. "You better enjoy this moment," I said on Tuesday, because it's unlikely a moment like this will ever come again.

Moving forward, I think I'm going to have to create an annotated printout of Baraka's poem, so that the students have a way of understanding more of the references, and also as a way of adding reflections on some of their responses to the poem over the years.

Related: