By Sequoia Maner

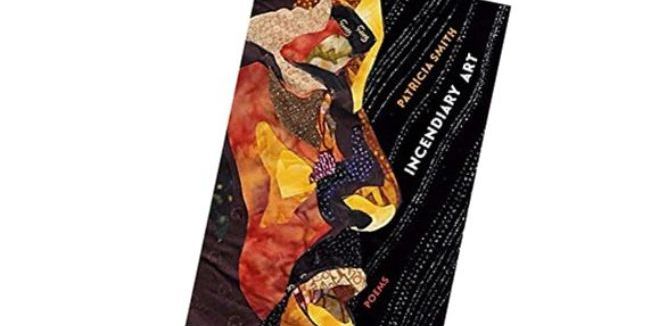

Patricia Smith’s newest collection of poems, Incendiary Art (2017), is breathtaking. Is bereavement. Is blues. Is balm. Is body. Is bullet. Is blaze.

Smith, long-lauded for her mastery of and fluidity within form and performance, has written a lasting collection that exhibits the products of a black woman’s laborious unpacking of white supremacist racism and the many ways the black body is made breathless; how “A black boy can fold his whole tired self around a bullet.” Composed for mothers who have lost their sons and daughters, the poet insists,

black livesIncendiary Art is black art for a time when black art is vital.

matter

most when they are in

motion, the hurtle and reverb

matter the rushed melody of fist

the shudderings of a scorched

throat matter

the engine that moves us

toward

each damnable dawn

matters

Today we are surviving another wave of neo-Fascist, anti-black terrorism and, in weaving together civil uprising and the bittersweet lamentations of victim’s mother’s, Smith captures just what it feels like to be “up to [our] necks in fuel”; up to our necks in in all this violence and all this grief.

As the poet writes, “Who knew our / pudgy American dream was so combustible?”

In my favorite series within Incendiary Art, Smith returns to narrative of Emmett Till (a move of so many poets), with sonnets that take the form of Choose-Your-Own-Adventure tales—a form that ritually returns the reader to the muted horror of fourteen-year old Till’s amputated adolescence.

Turn to page 14 if Emmett travels to Nebraska instead of Mississippi.

Turn to page 19 if Hedy Lamarr was actually Emmett’s girlfriend.

Turn to page 27 if Emmett’s casket was closed instead.

Turn to page 48 if Emmett Till’s body is never found.

Turn to page 128 if Emmett Till never set foot in the damned store.

The sonnets that follow these prompts are imaginatively impactful.

Incidendiary Art is structured by four sections. Part I, Incendiary, introduces the poet’s reoccurring reflection on riots—Chicago, 1968; Los Angeles, 1992; Ferguson, 2014—and other moments of inferno in African American history like the bombings of MOVE headquarters in Philadelphia, 1985 and the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, 1963. Part II, When Black Men Drown Their Daughters, lyricizes two New Jersey events where men drowned their daughters, one throwing her over a bridge from a car window. These poems dare not look away at black girls and black women (: “I loved her beauty. I loved her unkilled”).

Part III, Accidental, visits the narratives of black women and men who have “accidentally” died in police custody—whether winding up shot to death though handcuffed, or executed after mistaking pills/cellphones/nothing for a gun, or tasered to death after claims of superhuman strength or, or, or. As the poet repeats page after page, “The gun said: I just had an accident.” Part IV, Shooting into the Mirror, ties together all of these narratives with a moving elegy to her father that asks readers to think through how healing/exorcising father-daughter relationships is metaphor for healing/exorcising the nation and its illnesses.

Smith warns, “All our rampant hunger tricks / us into thinking we can dare dismiss / the thing men do to boulevards, the wicks / their bodies be.”

Scholars will be compelled to contrast Smith’s poems to Rankine’s Citizen: An American Lyric (2014) given that both authors have produced full-length collections grounded in the racial events of our Obama-Trump years. Equally deserving of wide-readership and critical acclaim, I suggest that Incendiary Art does different, equally-important work in the world—a claim that I offer you to take up, and perhaps one that I will follow up with in a Part II.

-------------

Sequoia Maner is a poet-scholar at the University of Texas, Austin.

1 comment:

Review makes me want to run to a bookstore to get my hands on Incendiary Arts.

Post a Comment